What is Pulse Feeding & can I use it to maximise Muscle Growth?

Maximizing Muscle Growth with Protein Pulse Feeding: The Role of Whey, Casein & Blended Protein Supplements

What is Pulse Feeding?

By Brian Batcheldor

Optimising Protein Intake – Introduction

In the sports nutrition arena, optimizing protein intake is considered paramount for enhancing muscle growth, recovery, and performance. This means utilizing a diet, protocol or product that results in maximal muscle protein synthesis (MPS) and increased net protein balance (NPB), but at a lower metabolic cost and with less unwanted byproducts or side effects.

The standard template for bodybuilders has always been multiple feedings spread over the day, with each being spaced around 3 hours apart. We’ve seen the daily intake creep up from the gram per pound of bodyweight advocated through the pages of iconic hardcopy bodybuilding media (Flex, Ironman, Muscular Development) in the 80’s and 90’s to sometimes more than double this today, courtesy of “bro science” posted on gear dealing sites or dispensed by “prep coaches”. It is common practice to see this stretched over as much as 8 feedings, often with the help of liquidised meals or waking in the night to squeeze more in. I want to revisit the practicalities, pros and cons and the potential fallout from this practice at a later date, it is simply beyond the scope of a single article and would also drift away from my intended topic of Pulse Feeding. For now, let us just say that the diet of today’s elite level bodybuilder compares to the diet required for dietary protein optimisation in the same way that crawling around town all day in your car during congestion has the same impact on it as doing the speed limit on an empty motorway to the next city.

One emerging dietary intervention that has garnered attention in recent years is Protein Pulse Feeding. This protocol was popularised by the studies by M A Arnal and colleagues at the National Institute of Agronomic Research, in Clermont-Ferrand, France. Their findings underscore the significance of protein (intake) timing and frequency in eliciting an optimal anabolic response, this was achieved by comparing two approaches:

- Consuming four equal doses of protein evenly spread throughout the day to maximize MPS and promote muscle hypertrophy

- Following a “Pulse Feeding” protocol, where 79% of the daily protein intake was given at 1200 and the remainder was split between 0800 (7%) and 2000 (14%)

* It is worth noting that the team behind this weren’t shy when it came to the protein intake itself, working with 1.7 grams/kg as the guideline in both protocols, way above what’s usually used in this demographic.

Why was Arnal and her team so heavily focussed on this relationship between nitrogen balance and the timing of protein intake? Nitrogen balance is a crucial measure in assessing protein metabolism, as it reflects the difference between nitrogen intake (primarily from dietary protein) and nitrogen excretion (primarily through urine and faeces). A positive nitrogen balance indicates that protein intake exceeds protein loss, which is essential for muscle protein synthesis and maintenance, the fine line between anabolism and catabolism that we always refer to. Of course, It’s important to remember that even when protein intake exceeds protein loss, non-dietary factors will also play their part in what side of that line you sit, training, rest, stress, drugs, illness, etc.

This initial study found that pulse feeding of protein significantly increased muscle protein synthesis rates compared to the evenly distributed intake pattern. This suggests that concentrating protein intake in fewer, larger meals may be more effective in stimulating muscle protein synthesis, particularly in older individuals who face unique challenges in protein metabolism, such as a blunted muscle protein synthetic response to protein ingestion compared to younger (non-training) counterparts, necessitating higher protein doses or more frequent feedings. This diminished responsiveness stems from factors such as age-related declines in hormonal function and muscle mass and changes in the ability to readjust stomach pH between feedings. Most importantly, this particular study alludes to there being an optimal timing for protein consumption to maximize nitrogen retention and thus support muscle protein synthesis. By concentrating protein intake at a specific time (in this case, at noon), individuals may better utilize dietary protein for muscle repair and growth, leading to this more positive nitrogen balance.

Okay, time to address the elephant in the room, elderly subjects, what has this got to do with you? I’ll concede that there are some nuances, but there is far more common ground and a much smaller margin for error with these subjects.

Drawing the Parallels; the Usual Suspects

- In post-workout recovery, exercise-induced muscle damage triggers catabolic processes to break down damaged proteins and initiate muscle repair. Similarly, in elderly/compromised individuals experiencing muscle atrophy during bed rest, disuse leads to the activation of catabolic pathways as muscle protein breakdown starts to exceed synthesis.

- There is an overlap in these catabolic pathways and the genes involved in both scenarios of post-workout muscle recovery and muscle atrophy during bed rest in elderly/compromised individuals. For example, both situations involve the activation of the ubiquitin-proteasome system (UPS) and the autophagy-lysosome pathway, which are responsible for degrading damaged or unnecessary proteins.

- Key genes involved in both pathways include those encoding components of the UPS such as ubiquitin ligases (e.g., Atrogin-1/MAFbx) and autophagy-related genes (e.g., LC3, Beclin-1). These genes regulate protein degradation and turnover in response to various stimuli, including exercise and disuse. Understanding the shared molecular mechanisms underlying these processes may provide us with targeted nutritional interventions or exercise protocols.to mitigate muscle loss and enhance recovery in both scenarios, such as Protein Pulse Feeding, Protein Intake Cycling and training periodization.

- In both cases, protein quality and timing are critical. Consuming protein-rich foods and/or high-quality protein supplements/amino acids post-exercise enhances muscle protein synthesis. Whilst spreading protein intake evenly throughout the day was believed to be the best way to aid muscle preservation in bedridden patients, we now know that there is likely a better way, a way that also lends itself perfectly to meeting the demands of strength athletes and natural bodybuilders alike.

Now that you have reviewed the above comparisons, you may want to ask yourself how much similarity you share with the genetically gifted Olympia competitor whose diet you’ve been following. Much of the advice about high protein diets that has made its way to us over the years has filtered down from early research in the nutritional treatment of alcoholic liver disease, where higher intake correlated with improved hepatic encephalopathy and breaking it down into small regular feedings mitigated ammonia build up. This research has been extrapolated to bodybuilders with a far higher protein intake in recognition of the transient nature of MPS, which peaks shortly after protein consumption and returns to baseline levels within a few hours. Employing the same multiple protein feeding system to sustain an elevated MPS over an extended period is probably a tall order when you get into the protein intake of a dedicated bodybuilder. Much of the data relating to the process of MPS factors in the influence of endogenous anabolic hormones (GH, IGF-1, testosterone), but this is far too small and transient to augment the process to the required degree with this kind of intake. The high dosages and steady state plasma levels of modern drug cycles permit optimisation of the most ill-conceived plan and then bang, – just like that, -positive nitrogen balance is now almost on tap. However, for the performance athlete (think strongman, thrower, weigh/powerlifter) this kind of approach is not only inconvenient, but it can also actually negatively impact performance, -something I have witnessed many times. Ironically, even an assisted heavy strength athlete will have to dig deep into his recuperative reserves when his organs are working around the clock shuttling enzymes, cytokines, growth factors and a whole host of other compounds around his body to address huge, often unpredictable, macronutrient challenges. A routine that could typically be comprised of multiple sessions of resistance training, event training, cardio and other allied work (sprints, jumps, etc) can easily lead to prolonged soreness, fatigue, loss of focus, insomnia, GI distress, breakdowns in technique and other unpleasant side effects when the athlete is under this kind of dietary duress. In real terms, his main event has now become eating, the body has committed itself full time to the process of digestion, training is now a secondary pursuit. Of course, it goes without saying that for a natural athlete, smarter research-based optimisation and experimentation are the only realistic options (pulse feeding?).

It would be only fair to point out that in a subsequent study using young healthy women, Arnal found that the advantages were not as profound. We shouldn’t overlook that the protein intake itself may have been enough to induce similar favourable outcomes, this was way higher than their regular dietary intake. The 2 diets were also only followed for 14 days, it may have needed longer for the required adaptations in the younger group. We don’t really know if some sort of ceiling may have been reached at 14 days and further increase could have separated the groups or how exercise would have impacted the results or even if or for how long any changes persisted.

One of several newer additions to the concept, a 2013 study by Olivier Bouillanne et al. further explored the concept of pulse feeding, this time using a slightly lower protein intake but with virtually the same split and over a longer period (6 weeks). It essentially asked exactly the same questions and identified exactly the same machinery at work behind the devastating muscle protein breakdown and functional decline (Sarcopenia). It also came up with the same favourable response to Protein Pulse Feeding, with a more profound effect on Lean Body Mass (LBM). A follow up study by the team in 2014 had very similar findings but also confirmed that the increased post prandial (the period after eating) amino acid bioavailability was still fully maintained at 6 weeks, i.e. protein turnover modifications persisted. It’s plausible that the improvements in nitrogen balance observed in Arnal’s study or the enhanced muscle protein synthesis rates seen in the Bouillanne study may be sustained over the long term with continued adherence to the respective dietary patterns. Whilst additional research is needed to elucidate the durability of these effects beyond the study duration, we could probably question that urgency in light of this being a protocol that would be factored into a periodised (training and/or otherwise) regimen. Whilst it’s probably prudent to consider the potentially transient nature of these effects, my own observation is that this approach has pretty much stood up to integrity in the athletes that I have applied it to, certainly being way more practical than the alternative. As I pointed out earlier, protein turnover is a dynamic process influenced not only by dietary factors but also by the various physiological and environmental factors of your specific event and lifestyle. A recurring theme that would have often excluded pulse feeding as a viable option in the past is the misguided belief that we are simply not set up to efficiently use the large protein feedings associated with this approach. Time and research have shown us many times that the 30 gram model is an urban myth and that we are not only capable but actually better suited in certain circumstances to consume much higher intakes. Under the right conditions, studies have demonstrated a far greater and more sustained anabolic response to a 100 gram protein feeding (source MPC) than a 25 gram one. There is plenty of research out there advocating that we give this practice a shot in order to be sure of reaching the required daily intake to preserve muscle mass, enable repair and support adaptation. Some research even supports the hypothesis that a blunted synthetic rate in older age is questionable if you are consistently proactive in addressing your optimal daily intake.

What is Pulse Feeding? – Hitting the Numbers with Protein Supplements

Yves Boirie, the professor behind the pivotal studies on dietary fast and slow proteins, which explored the differences in protein synthesis and net protein balance between whey and casein, had also specifically identified the unique EAA content of whey protein and labelled it as “a fast protein with optimal nutrition for the elderly”. In Arnal’s work investigating how long protein turnover modifications extended after a pulse feeding protocol her institute collaborated with Boirie and his team. It was clear that the previous findings of Boirie and his team would be utilised by others in inducing the established modifications in protein metabolism. From this collective research obvious deductions about the two milk-derived proteins could be made and applied. Whey protein, renowned for its rapid digestion and high leucine content, is well-suited for promoting immediate postprandial MPS and muscle recovery, particularly following exercise. Conversely, casein offers a slow and sustained release of amino acids, making it an ideal choice for providing a prolonged source of protein during extended periods of fasting or between meals. Casein’s unique gel-forming properties in the stomach result in delayed gastric emptying and a gradual release of amino acids into the bloodstream over several hours.

By combining whey and casein proteins, blended supplements provide both immediate and prolonged sources of amino acids, thereby supporting MPS over an extended period. This combination of fast- and slow-digesting proteins may optimize the anabolic response to protein intake, leading to greater gains in lean muscle mass and improved recovery compared to single-source protein supplements. Moreover, blended protein supplements ensure a steady influx of amino acids throughout the day, making them well-suited for inclusion in a protein pulse feeding protocol. By strategically timing blended protein supplementation, it’s possible to maintain an anabolic environment and support muscle protein synthesis during periods of fasting (bedtime?) or between meals (the XXL 1200 hrs feed!). Indeed, it is no coincidence that a study I mentioned earlier used a Milk Protein Concentrate ((whey + casein) to provide its 100 gram protein feeding (Tremmelen J et al). As previously established, incorporating blended protein supplements into a pulse feeding protocol certainly offers advantages to older athletes (40+) in tackling their specific challenges, i.e. blunted synthetic rate and upregulation of genes involved in catabolism.

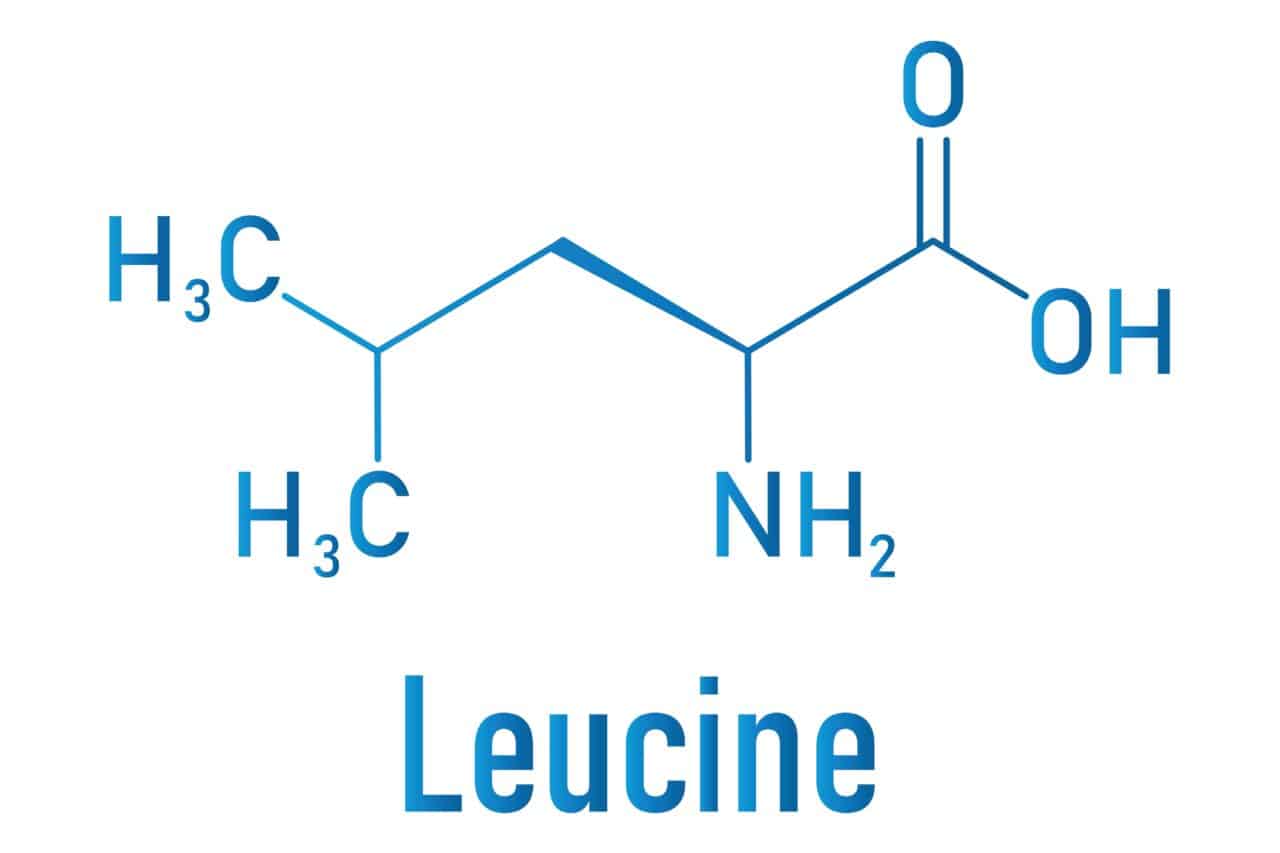

A Note on Leucine

Leucine serves as a potent stimulator of MPS, acting as a trigger for the mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) signalling pathway, which regulates protein synthesis in muscle cells. Research has shown that, even when consumed alone, leucine supplementation can substantially enhance MPS and promote muscle protein accretion, particularly when taken alongside resistance exercise.

A big factor in the efficacy of quality dairy proteins is that their combination ensures sufficient leucine content to stimulate maximal MPS stimulation, -particularly beneficial in the post-workout window and in older or compromised athletes, for which the existence of a leucine threshold has been scientifically established, -the amount required to maximize the anabolic response to protein ingestion. Moreover, in their dairy peptide form, leucine peptides exert additional metabolic effects beyond MPS, such as improving insulin.

Conclusion

Protein pulse feeding represents a valuable dietary strategy for optimizing muscle growth, recovery, and performance by strategically timing protein intake to maximize MPS. Whey and casein protein supplements, whether used individually or more synergistically as a blended supplement (as in Time 4 Whey Protein Professional), can be effectively incorporated into a protein pulse feeding protocol to support muscle protein synthesis and promote muscle.